Sun Starts to Set for California’s Surf Line

Rising Sea Levels and Coast Erosion Caused by Climate Change Put Scenic Oceanfront Route in Peril

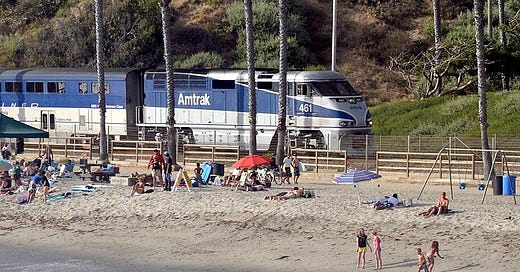

The Surf Line between Orange County, California, and San Diego is one of the most scenic rail lines in the United States. It runs for miles alongside the Pacific Ocean, sometimes just a few feet from the water. It is also one of the busiest with Amtrak’s Pacific Surfliner, Metrolink’s Orange County and Inland Empire- Lines/Orange County lines, the San Diego Coaster, and BNSF freight trains sharing the rails.

The railroad has stood the test of time since 1887, defying countless storms that battered the shoreline. However, rising sea levels and stronger storms caused by climate change have weakened its defenses. Recently, mudslides and coastal erosion caused several lengthy shutdowns requiring nearly $120 million to repair. Now officials want to reroute the line away from the coast.

In San Clemente, the track runs between the narrow beachfront and unstable sandstone cliffs. Since September 2022 passenger service was suspended three times. The longest disruption lasted six months.

To stabilize the railroad contractors had to drill steel anchors into the bedrock of the bluffs and bring in 18,000 tons of boulders. In June Orange County Transportation Authority (OCTA), which owns the right of way, declared an emergency to speed up construction of a temporary wall at the foot of the cliff. The two projects cost nearly $20 million combined.

Short-term solutions might keep trains running for a while but they cannot solve the ultimate problem – geographic instability caused by climate change.

In Delmar, the Surf Line runs for 1.7 miles on a bluff that overlooks the beach and ocean. Between 2018 and 2021 seven slope failures disrupted rail service. More than $100 million has been spent since 2002 to keep the railroad running. Meanwhile the coast line is eroding at the rate of six inches per year.

Short-term solutions might keep trains running for a while but they cannot solve the ultimate problem – geographic instability caused by climate change. That instability will worsen as bluff failures and beach erosion become chronic, according to Patrick Barnard, research director of the USGS Climate Impacts and Coastal Processes Team.

The service outages came as all three passenger carriers were still rebuilding ridership following the COVID-19 pandemic. During the first San Clemente line closure Pacific Surfliner ridership dropped from 70 – 75 percent of the pre-Covid level to 40 – 50 percent, according to Jason Jewell, managing director of the LOSSAN Rail Corridor Agency, the joint powers authority that manages the Pacific Surfliner. The corridor stretches 351 miles from San Diego to San Luis Obispo.

Pacific Surfliner farebox recovery was hovering around 35 – 40 percent last Spring, which is below the 50 percent threshold mandated by the state of California. Just prior to the pandemic it was at 80 percent, Mr. Jewell stated at a state senate subcommittee hearing in May.

Unlike Henry Flagler’s Key West Extension, which was wiped out in a 1935 hurricane, the Surf Line is too important to be abandoned. It is San Diego’s only active rail link to the rest of the United States and eight million travelers annually ride the Amtrak, Metrolink, and Coaster trains that use it. The Pacific Surfliner is Amtrak’s second busiest line.

In addition, the Surf Line plays a small, but significant, role in the railroad freight network. The Pentagon ships approximately 2,000 pieces of military equipment annually by train to and from the Port of San Diego, and the Surf Line is part of the Department of Defense Strategic Rail Corridor network. During the first ten months of 2023, BNSF hauled 146,000 motor vehicles – roughly ten percent of the cars sold in the western United States – from the port

Relocating the oceanfront segments in Delmar and San Clemente “is the only viable solution” for keeping the line open, according to state Sen. Catherine Blakespear, chair of the Senate Transportation Committee Subcommittee on LOSSAN Corridor Resiliency. “The alternative is endlessly spending money on a losing ‘protect in place’ strategy.”

A move inland would make the Surf Line less scenic but it would also improve reliability, travel times, and competitiveness vis-a-vis driving. However, relocating the two segments comes with a combined $8 billion price tag, according to preliminary estimates.

In 2022 the San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG) received a $300 million grant from the California Transit and Intercity Rail Capital program for preliminary engineering and preparing environmental documents to relocate the line through Delmar. A draft blueprint estimates the project would cost around $3 billion, but it would be less expensive than continually rebuilding and fortifying the track.

Relocation will require digging a tunnel under parts of Delmar but stakeholders have yet to achieve consensus on where it should be located. SANDAG had narrowed the proposed routes to two finalists but Delmar residents objected to locating the tunnel under their homes.

The Delmar City Council adopted a “guiding principles statement” that calls for the rail line to be rerouted to a tunnel adjacent to Interstate 5 or the Delmar Fairgrounds. Planners ruled out I-5 as too far out of the way and too costly. The 22nd District Agricultural Association objected to the fairgrounds routing because it would not be a good fit with a future affordable housing project.

SANDAG planners have produced a “spaghetti map” with a dozen possible routes and they expect to conduct more studies, public meetings, and outreach before choosing a final alignment. The project timeline calls for final design work to begin in 2026, construction in 2028, and completion by 2035.

In August, the Orange County Transportation Authority (OCTA) launched a $5 million study to investigate the cost and implications of relocating approximately 11 miles of rail line around San Clemente. The study will bring together technical experts and public agency partners to engage with stakeholders to pinpoint issues that impact the corridor and solutions to protect it. Preliminary estimates put the cost of the San Clemente project at roughly $5 billion.

At hearings held by Senator Blakespear’s subcommittee witnesses representing Orange and San Diego Counties stressed the need to expedite relocation of the imperiled tracks. OCTA Chief Executive Officer Darrell Johnson told the subcommittee that San Clemente’s beaches had already lost 20 feet of sand.

State and local officials will have to consider spending billions on the corridor in coming years not only for relocating the two oceanfront segments. A report by Senate researchers released ahead of the hearing said $20 billion would be needed to completely make the line safer, faster, and easier to use.

LOSSAN Corridor administrators, supporters, and state legislators need to also address governance and operational issues that often make getting things done difficult. The corridor runs through six counties. Three passenger railroads and two freight railroads run over it. Seven different entities from both the public and private sectors, each with their own agendas, own different parts of the right of way.

In his testimony, OCTA’s Johnson highlighted the lack of a clear process for handling emergencies on publicly owned and operated railroads. The California Transportation Commission first has to declare an emergency in order to authorize funds to cover repairs. “There isn’t any one agency in charge of fixing the problems,” he added.

"The longer we take, the more expensive it becomes," testified Katrina Foley, supervisor for Orange County’s Fifth District. “We need more than the piecemeal, reactive planning that has taken place over last decade. My hope is that this committee will prioritize pulling everyone together towards a long-term planning process.”

Senator Blakespear expressed concern that the lack of someone in a position to make decisions could lead to balkanization. “It’s a corridor and hyperlocal concerns are only one aspect,” she said. “It needs to function for the whole 351 miles.”

Ad hoc planning hinders LOSSAN’s ability to compete for grants from the $20 billion for passenger rail projects in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 (Bipartisan Infrastructure Law). Without a comprehensive, strategic, capital investment plan in place it will be harder for LOSSAN to get the funding it needs to relocate the tracks and upgrade the line.

“We have to make the case for our federal partners that we know what we’re going to do and what effect it’s going to have,” Senator Blakespear said. “We’re not there yet.”

Might I remind folks of the process or provision known as eminent domain. A community may rail against the suggestion of a tunnel being bored under it. Okay, I get that. But, as long as land stability isn’t compromised and ground movement isn’t a factor, this should be no big deal. That can be tested for. What’s in the best public interest is what needs to be considered here.

Moreover, all things considered, one needs to ask what route would be the least disruptive. When highways get built, these seem to go in unopposed. I don’t understand why rail is held to a higher standard. At least, that’s how I see it.

Comes the expense. On a 218-mile-long high-speed rail line planned for Las Vegas, NV to Rancho Cucamonga, CA., construction is to purportedly begin this year, all at a projected cost of $12 billion. A major pass - Cajon - will need to be passed through to reach the latter community from the Victor Valley. This presupposes there will be tunneling involved. In rerouting the LOSSAN Corridor around San Clemente (coupled with other line relocation work - I don’t know how many miles are involved in all), if that’s what the prescribed fix involves on the other hand, if I’ve got this straight, the $20 billion figure seems excessive.

Regardless, whatever amount it ends up costing, BNSF should at the very least have no qualms about paying its fair share. It does, after all, use this line.

Over the years I drove US 101, I always wondered how long this line could survive in its current location. It is truly one of the most beautiful lines in the country.